TEMPO.CO, Jakarta - Every year, when we celebrate Independence Day, we always need Chairil Anwar, who was boorish but produced brilliant and new works. His poems are read from Meulaboh to Merauke. Chairil Anwar is like a part of the Indonesian nation that once existed and is still missed.

Chairil lived and worked at a time of seething nationalism, when hopes that the independence promised by the Japanese were followed by armed struggle in response to the aggression of the two Dutch "police actions" In the midst of these revolutionary times, between war and ideas of greatness and freedom, Chairil, who rebelled against the establishment, was seen as an alternative in every step this nation subsequently took.

During the New Order regime, which idealized uniformity, he was a symbol of untrammeled freedom, while in the reform era, when freedom of opinion became no longer the ideological foundation that dominated political parties, the 'depth' (the opposite of triviality and meaninglessness) that Chairil represented was still hoped for by many.

In Hoopla!, Chairil wrote about artists who needed to hold freedom in high esteem and to be fully prepared to face the risks, while criticizing their lives that were 'tranquil' and without meaning. He was convinced that it was freedom and risk that gave life meaning for artists and made a contribution to mankind.

In response to this stubbornness and dedication, poet Abdul Hadi W.M. wrote in the literary magazine Horison, underlining that, "What is interesting about Chairil Anwar is his vitality as a poet, his enthusiasm in his poetry that knows no political horse trading. He was prepared to sacrifice himself and suffer for the aims of his poetry that became one within him."

Chairil died young, at 27, and history records that he was a rebel who never grew old. Complications from a lung infection, stomach problems and syphilis according to many ended his wild bohemian life. But dying young has perpetuated his image as a rebel against the customs and traditions, values and establishment of avant-garde literary magazine Pujangga Baru. Like Beethoven in the musical world, Chairil Anwar has become a symbol of rebellion and renewal, not just in the world of poetry, but also language.

While Ludwig van Beethoven took music out of the Classical age into the Romantic era, Chairil led poetry and artists to discard the legacy of the Pujangga Baru generation and to adopt the new values of the pro-independence generation of '45. In contrast to the Pujangga Baru generation, which still seemed mesmerized by the mooi Indie series of paintings of idyllic Dutch East Indies landscapes, Chairil introduced words such as mampus (damn) and hambus (go to hell) borrowed from regional languages; coarse words more usually shouted as curses in markets or brothels, into his explosive poems.

He was a creature of the streets who was never tamed. Chairil was a true and complete rebel who united the words in his poems with daily actions. He was an individualist in a collectivist nation; he was ill-mannered in the midst of a society that appreciated politeness and a rebel against the values of the time. Chairil stole books from bookstores and copied the work of others, seemingly without any sense of shame. His poem Krawang-Bekasi, which touches those who read it, is believed to have copied The Young Dead Soldiers by American poet Archibald MacLeish. Literary critic and close friend H.B. Jassin accused Chairil of stealing the work of Chinese poet Xu Zhimo, which was translated into Datang Dara, Hilang Dara (A Girl Comes, A Girl Goes).

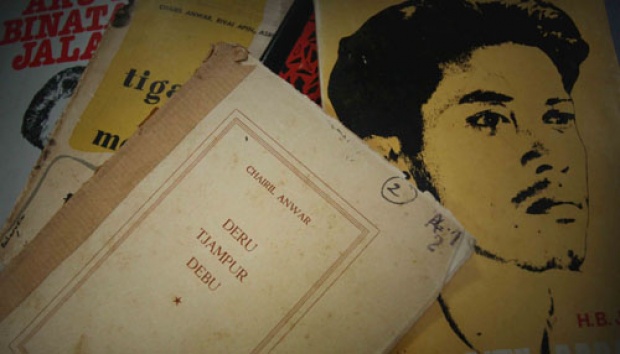

There is no denying that the poems of this young man whose works have used elements of world culture are contemplative and intense, the result of a long struggle to find the best words, diction, form and content in the wording. Chairil's hand-written manuscripts that have never been published, and which are stored in the H.B. Jassin Data Center at the Taman Ismail Marzuki arts center in Jakarta, show some of the poet's creative process. Full of crossings-out and corrections of words, written in pen or pencil, they represent the stages of a difficult struggle. They are a model the equal of which it is difficult to find in this instant digital age.

Chairil plagiarized, did not repay his debts to his friends, was obstinate and was fond of visiting brothels. But 67 years after his death, the greatness of his works has not faded. Chairil faced heavy criticism, but it seems that everybody is prepared to forgive him, because Chairil was a rebel, like a part of the Indonesian nation that once existed and is still missed. (*)

Read the full story in Tempo English Independence Day Special Edition