Like some feared heavyweight, Suharto’s account of what happened in 1965 has long been king of the ring. Schoolchildren still learn that on October 1 of that year, the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) orchestrated a coup against President Sukarno. When it failed, the people’s anger boiled over, and many citizens were killed.

Recently, though, a new narrative has emerged. This one calls into question Suharto’s basic claims about the events, and places the focus on what the official version downplays: that hundreds of thousands or millions of alleged communists were murdered in 1965-66 as a result of state policy. The army played a central role.

In the latter vein is 1965: Indonesia and the World, a book of essays that put the events in an international context. It comes in the wake of The Act of Killing, a landmark documentary about former death squad leaders who remain prominent in Indonesian society today, and follows an unprecedented report by the National Human Rights Commission (Komnas HAM), which found that crimes against humanity occurred and that the military was responsible.

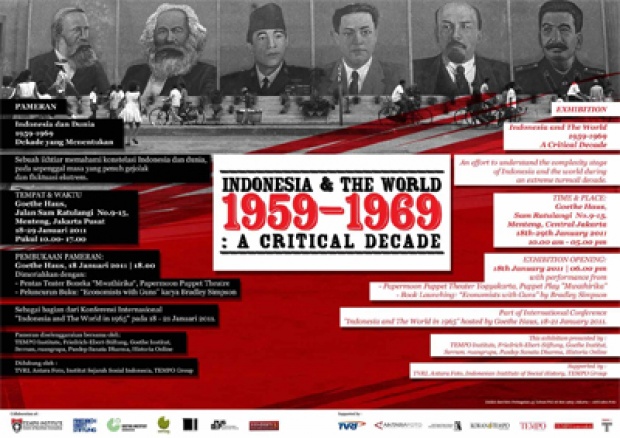

The book launched on the second night of Culture and Conflict, an event series put on from September 29 to October 6 by the Jakarta branch of the Goethe Institute, the German cultural center operating worldwide. It was accompanied by a discussion. Bernd Schaefer and Baskara Wardaya, the book’s editors, sat onstage with five Indonesian intellectuals. One of them was Ratna Hapsari, head of the Indonesian History Teachers Association. She said Suharto’s New Order regime had shaped Indonesia’s collective memory through propagandist monuments, museums and movies.

“This book divulges new information that has previously been suppressed by the government,” Ratna said in Indonesian, a translator giving her words in English. “History classes always only referred to one source: the government narrative, Suharto as savior.”

Like the discussion, the essays are presented in both languages. This is perhaps the book's greatest strength. The facts it contains could generally already be found by anyone with an internet connection who knows where to look. But its great utility is the way it brings those facts together into one package, able to be understood by speakers of English and Indonesian alike.

Much of the material will be controversial in today’s Indonesia. One of the essays is by John Roosa, whose Pretext for Mass Murder (2006) was banned by the Attorney General’s Office (AGO) in 2009 (it was later reinstated as the result of a court case which revoked the AGO’s authority to ban books). The essay provides an alternative account of the September 30 Movement (G30S), the alleged PKI coup attempt. It argues that the PKI did not mastermind the coup, as Suharto claimed, and that Suharto and his allies in the army organized the killings that followed.

Most of the other essays examine different countries’ relations with Indonesia at the time. Bradley Simpson, a history professor from Princeton University, draws on declassified documents to show how United States officials, far from condemning the massacres, eagerly assisted. The Americans, desirous of Indonesia's natural resources and allergic to communists everywhere, supplied Suharto’s army with equipment, food and weapons. “No one cared, as long as they were communists, that they were being butchered,” US State Department official Howard Federspiel is quoted as saying.

German scholars Jovan Cavoski, Ragna Boden and Schaefer consider communist China, Soviet Russia and East and West Germany respectively, especially in the context of the Sino-Soviet split. The PKI was pro-Chinese; meanwhile Indonesia owed Russia a lot of money. When the killings broke out, the Soviets were more concerned about reaching an understanding with the generals on Indonesia’s loan debts than with confronting them about the PKI. Had the PKI been in Russia’s rather than in China’s camp, Schaefer wonders, perhaps the army could not have exercised such brutality against it.

It was rather bold for a foreign organization, a cultural institute no less, to address this issue. Indonesian rabble-rousers often play the “foreign meddlers” card, still potent in a country where colonists reigned for centuries. But there are Germans who evidently view it as their role to help other nations come to terms with their past, as their own society was forced to do after Hitler’s pogroms. “Not a year went by where we didn’t talk about it in school,” Goethe Jakarta’s Head of Cultural Programs Katrin Sohns said in her opening speech. “Over time, I watched the discourse change and widen.”

For some at the event, there was hope the book would help Indonesia down a similar path.

“Now we just have to figure out how to get the president and the Supreme Court to read it,” Putu Oka Sukanta, a writer and poet, said at the discussion.

PHILIP JACOBSON